I’m back from a short and sweet trip into the Algonquin backcountry. Only one canoe and two paddlers this time since everyone is in an altered state this year: pregnant, sick, pregnant, breastfeeding (me). 26-week pregnant Allison and I paddled to a Hemlock covered and surprisingly secluded site on Ragged Lake. With five backcountry camping trips behind me and countless car camping or cottage trips to the same general area of Ontario, I’ve been thinking about the way there - the car ride, the pit stops, the highways, and the scenery along the way.

Ship yourself upstream

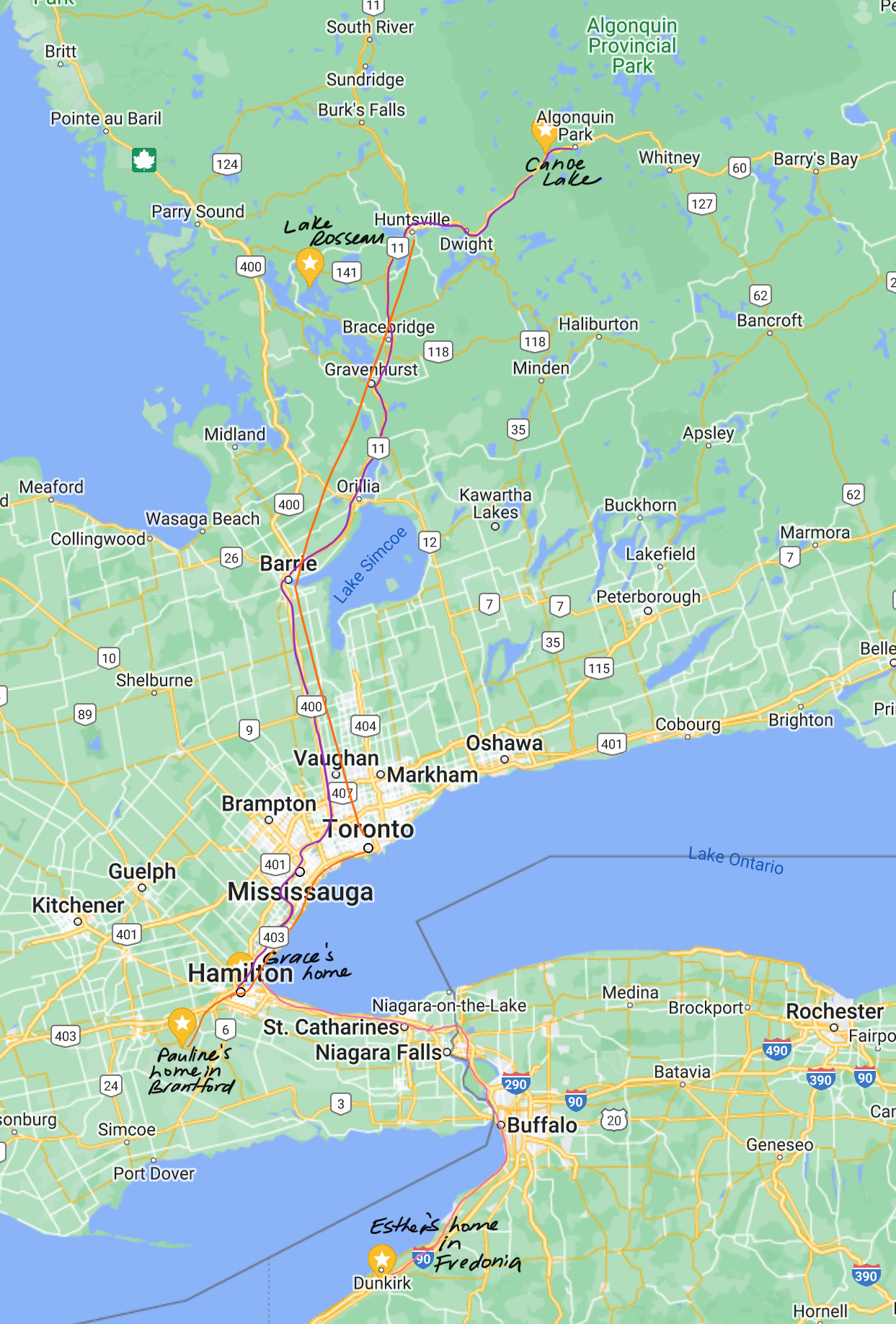

The routes that Pauline (paddling in the 1890’s), Esther (1930’s) and I have taken to access the backcountry are so similar and so different at the same time. We’re all moving north between the Great Lakes, and when I mapped it out (see below) I was reminded that the general shape of the route is very similar.

But a lot looks different, starting with the method of travel. Pauline traveled by train, and Esther used a combination of trains and cars. Coming from upstate New York, her route changed dramatically with the development of new, faster highways. From southern Ontario most of the ride takes place on three highways: Highway 400 (completed in 1952), Highway 11 (extended in 1937) and to Algonquin, Highway 60 (completed in 1936). I’ve exclusively traveled by car from dense sprawl, to what Southern Ontarians call cottage country.

Pauline Johnson (1861-1913) traveled by train to Muskoka to trip with her pals in the 1890s. Her journey is the most mysterious to me as the train system in Ontario doesn’t exist in the same way anymore. In her prescriptive articles on canoeing she advised readers to “ship the canoes and yourselves upstream,” something she did through the 1890’s when she was in her thirties. She took the train from Brantford to Toronto, then Toronto to the Muskoka area, though most of the time she isn’t explicit about where exactly. She usually traveled by train to a hotel in the area, and then set off the next morning, such as in this trip:

“We started with our canoes and kit one warm hurried day in late April, and after a railway trip of ninety miles, during which we changed cars twice and waited some hours at a junction, we finally touched the edge of the great Nipessing [sic] district, and landed at the little lumbering village of S-, which sits garnished with saw logs and mills, on the edge of a calm lake showered with islands and girdled in solid granite. After a good night’s rest at a hotel you could scarcely call a palace, we arose with the sun, and launched forth to find the head of Ralph’s long-talked-of river.”

One of my favourite canoe stories from Pauline is a dramatic tale about putting her canoe in a canvas cover before stowing it away in the baggage car on the train home from a backcountry trip in Muskoka. She was already hot, frustrated and flustered because despite being a hotshot woman paddler at camp and winning the admiration of her pals, no one bothered to help her pack her canoe and get it on the train. She struggled but managed to get her canoe to the baggage car and herself aboard with her friends. Once they arrived home Pauline went to collect her canoe: “What should greet my horrified eyes but my beautiful canvas-packed darling beneath two commercial traveler's iron bound sample trunks, three stretchers, a box of tins, a crate of blueberries, two valises, a baby carriage, a bunch of lacrosse stocks, four bales of blankets, a basket of house plants and a bicycle.” She then watched the baggagemen drop her excavated canoe five feet below onto the platform. She “ejaculated a phrase not strictly feminine” and collected her canoe, which needed a large repair to fix the damage.

Esther Keyser (1915-2005) started a tripping business taking clients, mostly women, to camp in Algonquin Park in the 1930s. She lived in a small town called Fredonia in New York state, about 80 kilometers south of the Canadian border. As a young adult, she traveled to Algonquin before Highway 60 was completed in 1936. “The trip to the Park from Fredonia took almost two full days,” Esther wrote in her book. “The first day we drove to Orillia, Ontario, and spent the night in a local hotel. We awoke early the next morning to be sure we could make the drive to Scotia Junction, where the train for the Park left at 10 a.m. As trains left only three times a week for Algonquin Park, we could not afford to miss this connection.” The other passengers were miners, construction workers, fish guides, or traveling to jobs at logging camps. Esther and her two pals prompted curiosity and concern on the train: “We enjoyed this attention. And we liked the idea that not many women embarked on an expedition like ours… exploring an area known to a very small group of loggers, trappers, fishermen and rangers, but not known to most people interested in canoe camping adventures.”

Of the train from Scotia Junction to Algonquin Park, Esther wrote: “The tracks headed north through beautiful hardwood forests, along sparkling rivers and beside lakes of various shapes and sizes. There were marshes teeming with the activity of birds and animals and large outcroppings of Canadian Shield granite. How exhilarating it was to see this beautiful natural landscape and realize we were leaving civilization and all of its trappings behind.”

In 1936, after Highway 60 was completed, Smoke Lake was a 12-hour drive from Fredonia. Esther eventually had three children, and in 1951 her and her husband Joe wanted to take them to one of their favourite places in the park, Hogan Lake. But “their ages (eight, six and five) prevented us from covering the required miles in the available two weeks, Esther wrote. “Even though it stretched our budget we decided to fly in. The practice of using an air taxi to drop canoe parties into the middle of the Algonquin wilds has wisely been discontinued. It did, however, give us a means of introducing our children to one of our favourite lakes.”

I’ve only traveled by car to Algonquin. I remember being picked up by Emily at 6 am for my first trip. We packed the car as the sky started to lighten. I fastened my seatbelt while my husband smiled at us from the sidewalk. Well, Emily said. I guess we’re going! We were both so nervous.

In this modern age, we have the luxury of frequent gas stations, fast food options, even bathrooms we can use without purchasing anything at these massive anonymous rest stops called ONroute. I usually eat breakfast in the car, and when I drive with Emily she always brings hard boiled eggs for both of us. On the way home I’ve gotten in the habit of stopping at Webers on Highway 11 for a cheeseburger and chocolate milkshake.

If the defining aspect of Pauline and Esther’s journey to their canoe trips is time - one needed to be able to spare at least a day and night on either end just getting to the start of the trip - the defining aspect of my journey is traffic. I plan trips that span midweek to Monday in an attempt to avoid congestion around Toronto. Once the car gets past Barrie it’s smoother sailing but it always makes me feel a bit guilty. What are we doing? We, the people with pockets of time and disposable income enough to reserve campsites and book cottages and clog up the roads north of Toronto on a seasonal basis. What is the impact of all this traffic and development? I don’t have the answer; I keep going back for more, alongside everyone else.

Links

To Get Out of Your Head, Get Out of Your House: Spending time in nature can help relieve stress and anxiety. Arthur C. Brooks, The Atlantic

Lost in the wild: What it's like to watch a daring chopper rescue unfolding in Algonquin Park. Joseph Brean, National Post

Sorry Algonquin. Pairing negative reviews with stunning photographs of Algonquin Park. Photographs by Jesse & Susan Villemaire

Paddling her own canoe: The Algonquin journey of guide Esther Keyser. Patti Vipond, Parry Sound North Star. *Recent article about Esther!*

Hi Grace - interesting to reflect on the mode of transportation and the travel time committed to make a backcountry trip in those days. They seemed to find the space and time in their everyday lives to make this happen. Even more effort than I can imagine! Thanks for sharing, Deb