Hi! I'm Grace Evans and this is Dry Spell, my weekly letter of off-season reflections on canoeing.

I have developed preferences for the clothing I wear while paddling, and I was curious how my outfits compare to that of the two women canoeists I’m studying, Pauline and Esther, across our three different paddling eras. For all three of us, most of the paddling I’m looking closely at has taken place in Ontario in the summer.

Pauline, 1890’s

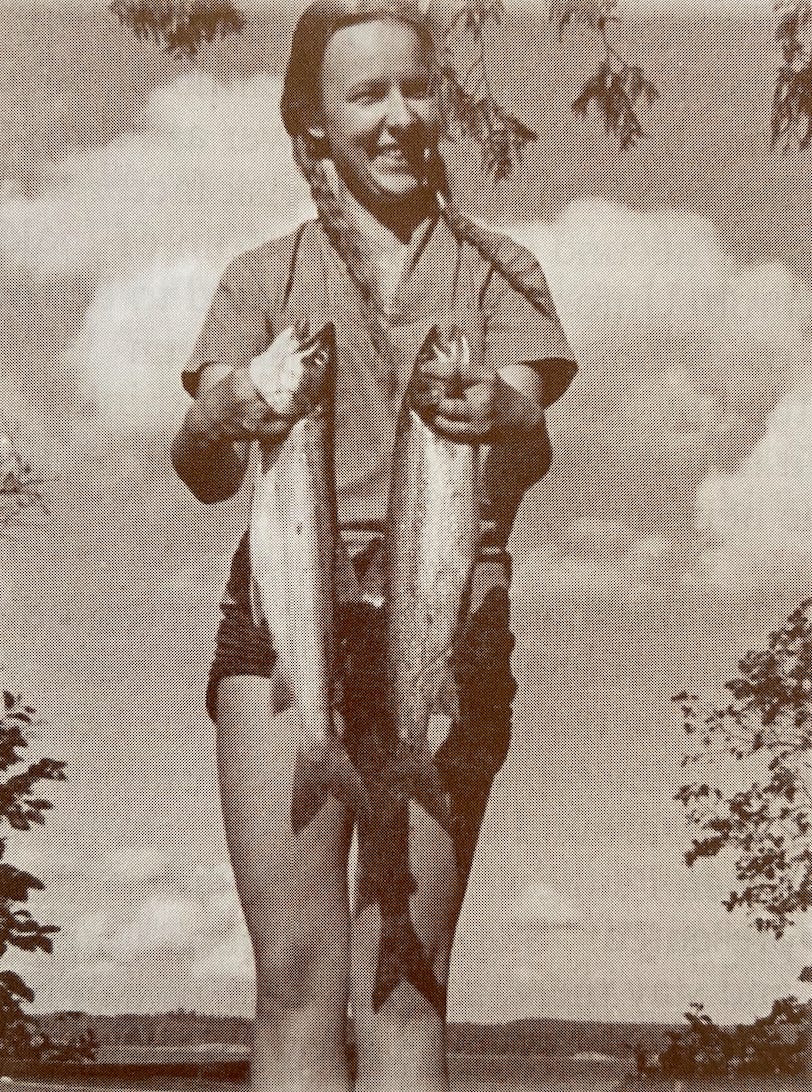

Pauline Johnson (1861-1913) is primarily known for her poetry and performance art, but I adore her canoe writing from the 1890’s. She paddled the Grand River where she grew up, and traveled by train to Muskoka to trip with her pals when she was in her thirties.

Pauline is usually pictured in a long sleeved shirt and a long skirt, with a tam o’shanter on her head. She describes her trunk after a backcountry trip as “full of the worst looking togs1, the dingiest flannels, the half dry bathing suit, three pairs of terrible looking shoes (they will do again for next year, you tell yourself), a hammock, some bath towels, a Tam, a fore-and-aft2, a cow's breakfast3, a gray check jocky4, and a striped flannel that matches your blazer.” This gives me a sense of some of the clothes she was packing, as does her description of “the canoeing girl:” “she wears tan shoes and flannel5 gowns during her weeks of outing.”

But Pauline’s trademark is the Tam o’shanter; in one of her essays she even goes so far as to declare: “I am addicted to tam o’shanters.” In mail-order catalogues there are a few ladies hats specified as bicycle tams, but most hats advertised as “Tam o’shanters” are geared towards the children’s market, and range from silk lined velvet or beaver to the more utilitarian pilot cloth6, of which I imagine Pauline’s was made of.

Esther, 1930’s

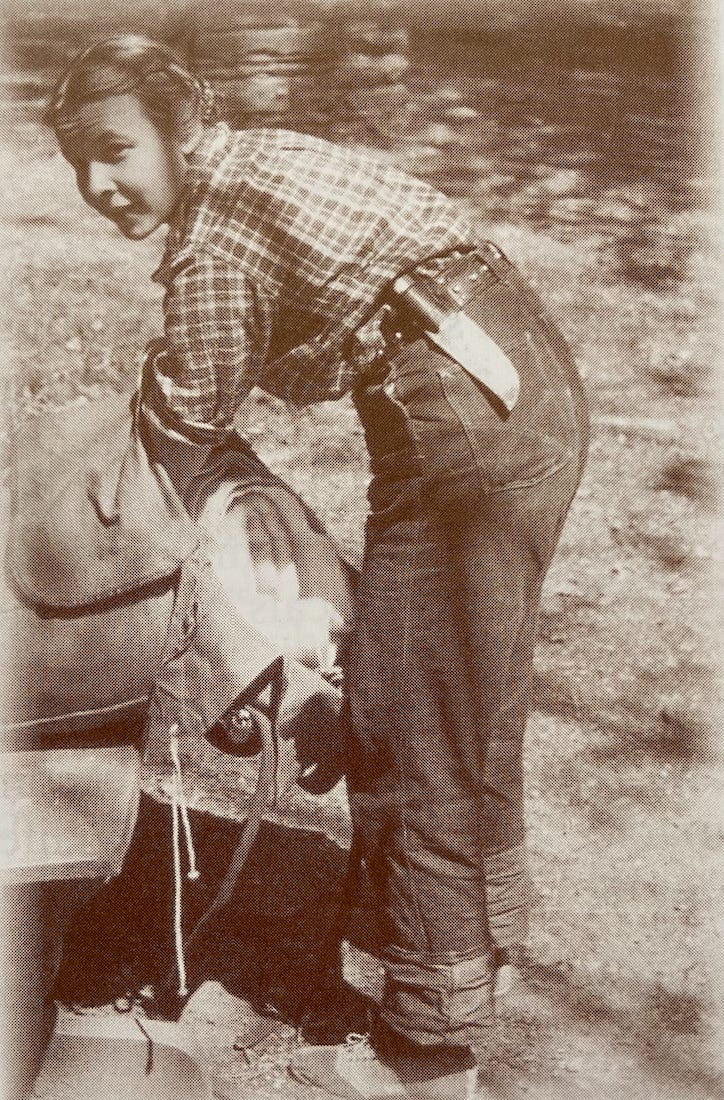

Esther Keyser (1915-2005) started a tripping business taking clients, mostly women, to camp in Algonquin Park.

Esther is usually pictured with her hair in braids or tucked into a small hat. She typically wears a long sleeve collared shirt with deeply cuffed jeans, a leather belt and slim little shoes. For guests attending some of her guided trips, she recommended: “A minimum of clothing was the rule, but sweaters, shirts, pants, knickers and socks made from wool were the preference. I also recommended a wide-brimmed felt hat to protect against the rain and sun, and one that fit well enough to be wind proof. We still depended on ponchos as our primary rain gear. Gore-tex and other fabrics now taken for granted were not available.” When they swam, they skinny dipped since they “brought no bathing suits, as they would have been especially heavy and impractical. The swim suits of that day were made of wool and covered most of the body.”

Grace, 2020’s

I usually wear quick dry everything - shorts and a t-shirt and a quick dry Tilley hat. I prioritize quick dry t-shirts that are SPF. For warmth I’m more likely to pack a fleece than wool because if it gets soaked I’ll be able to dry it out. I’ll pack one quick dry pair of pants and a fleece pair for the same reasons. I’m guessing the biggest difference in technical clothing between 1930 and now is rain protection, as Esther indicates, and quick dry materials. Whether my group wore bathing suits or not depended on proximity to other campsites and canoe traffic, as well as the level of desperation to cool off in the water. I was surprised to read that Pauline packed “three pairs of terrible looking shoes,” so including the shoes on her feet she had four pairs with her, but I suppose that makes sense if the shoes were less versatile and hard to dry out. I’ve worn Gore-tex hiking shoes and strapped hiking sandals to my bag, and in cooler climates I’ve worn my trusty Blundstones.

Perhaps the biggest difference in clothing and wearable gear, however, is that I always wear a PFD while paddling. I’m always surprised at how few people wear them, especially in the backcountry. Esther herself writes that in the 1930s “swimming wasn’t as popular as it is today, and far fewer people knew how to swim and were comfortable in the water.” 152 people fatally drown each year in Ontario according to the Lifesaving Society, and the majority of drownings happen within 15 metres of safety. It’s just not enough to know how to swim. Whether I’m in my local marsh which tops out at a metre deep, or backcountry, I’m grateful that we have the technology to have high quality personal flotation devices that aren’t too cumbersome to paddle in.

The differences between our wardrobes makes me think about how much higher the buy-in was to access nature in this way. In addition to having the leisure time and the funds, one really needed to want to be out there, simply because it sounds like less fun to sit in wet wool and lugging around multiple pairs of footwear, heavy clothing, and other more unwieldy gear. Or maybe it was that much more compelling since provincial parks and wild spaces were that much wilder, and less populated by people. Perhaps the true measure of the impact a backcountry tripper’s gear has on the enjoyment of their trip is in whether bathing suits are required, or not.

Thanks for reading Dry Spell. I’d love to know what you think; please feel free to leave a comment or reply to this email!

Togs: basically just old clothes

A fore-and-aft: a sail to rig up along the line of the keel, rather than perpendicular to it

A cow’s breakfast: possibly means a farmer’s straw hat

Jocky: I truly don’t know what this means yet

Flannel: does not reference the brushed cotton plaid modern readers might picture. Catalogues for the late 19th century recommend certain kinds of wool flannel in the fabric section for ladies’ skirts

Pilot cloth: a heavy twilled woolen overcoating with a thick nap used especially for seamen's blue uniforms